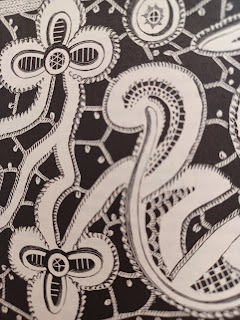

Having seen ‘imitation lace’ being described in my late 19 century needlework dictionary as a type of tape lace (see last week’s post) I was interested to see how Pat Earnshaw defined it. She wisely does not use the term imitation lace but does discuss copying and convergence in her book on the identification and care of bobbin and needle laces. She suggests seven possible permutations of copying, starting with ‘same time; different area; different technique’ in which she includes all the machine lace copies of different handmade lace techniques, such as machine-made Chantilly lace. Chantilly lace is the fine black lace seen in the image above and the handmade and machine-made versions are often difficult to tell apart. Initially I thought the example above was machine made because of the way the outlining has been done but on closer examination I found the lace had been made in fine strips, later joined together, which is a feature of handmade Chantilly lace.

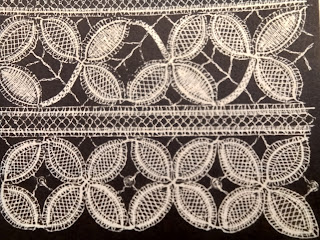

Under ‘same time; different area; same technique’ Pat

mentions the convergence between Bedfordshire lace and Maltese lace, as well as

that between Honiton and Brussels laces (image above). In ‘different time;

different area; same technique’ she includes the raised needlelaces of the 17

century, which were copied in the 19 century for sale and exhibition as well as

for the domestic lacemaker as we saw in my previous post about imitation lace. There

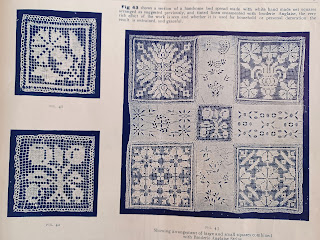

were also laces in the category ‘different time; different area; different technique’

such as the 16 century reticella designs that were copied in the 19 century using

the Schiffli machine. I think Pat Earnshaw has confirmed my original scepticism

about the label ‘imitation lace’. Most laces seem to be influenced by ideas and

techniques from other places, and as Pat suggests sometimes this is copying and

sometimes convergence. However it was always with the aim of selling more lace

to the consumer, by keeping up with fashions and making the lace more cost

effectively.