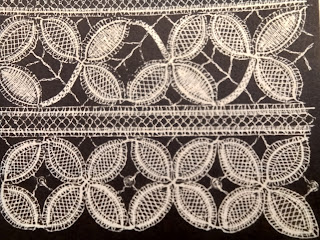

These lace trims were made in the 1960s on the Levers lace machine but they all have their origins in nineteenth century handmade lace. That is probably not surprising as a large part of the training for machine lace designers included copying old lace patterns and designing lace that appeared handmade. The fine little trim at the top resembles Buckinghamshire baby lace, a simple pattern that was one of the first a bobbin lacemaker would learn. The dainty black lace resembles Chantilly lace, a fine French handmade lace with an open net background and a design outlined with a thicker gimp thread. The two lower laces also resemble old Buckinghamshire bobbin lace designs, the upper one is similar to the sheep’s head pattern, another fairly simple handmade lace that a beginner would learn, and the lower one resembles floral lace, which was a much more complicated type of bobbin lace. Examples of these types of old bobbin lace patterns were kept by machine lace manufacturers in design portfolios specifically to inspire their designers and it’s interesting to see that these old designs were still inspiring lace in the second half of the twentieth century.

Thursday 22 December 2022

Friday 16 December 2022

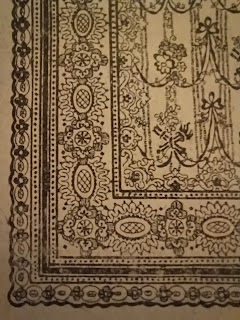

Draught for a machine lace curtain

This pattern holds the information needed to produce a lace curtain on the Nottingham lace curtain machine. This image shows the bottom half of the design and the one below shows the heading. The designer would have produced the original design and then passed that to the draughtsman who would have converted it into this series of tiny colour-coded squares. This draught would then have been passed to the card puncher who would have followed these instructions to punch out the jacquard cards that operated the threads on the machine. The squares are painted red, green or blue or left blank according to the thread movements. There was no standard system for the colours but in general red indicated back spool ties, green represented Swiss ties and blue represented combination ties.

The draught

also includes information on the fineness of the lace, in this case 10 point

which is a medium gauge, and the quality (54) which is a measure of how many

complete motions of the machine were required to make 3 inches of lace. I love

the way this pattern incorporates stylised swags and draping at the bottom

which would have required some skill on the part of the draughtsman to convert

from design into instructions for the machine. I also like the spotted net

between the main design at the bottom and the flowers at the heading which could

have been expanded by repeating that section to make curtains of varying

lengths. All in all a versatile and very pretty lace curtain.

Thursday 8 December 2022

Tawdry: St Audrey’s lace

To describe something as tawdry means it is worthless, vulgar, cheap or gaudy and it is a corruption of the term St Audrey’s lace. St Audrey was named Etheldrida when she was born in the seventh century. She was the daughter of the king of East Anglia and married the king of Northumbria so had a wealthy life, however, she renounced both her royal life and her husband and became a nun and ultimately a saint. She died in the year 679 with a throat tumour, which she considered God’s punishment for her love of necklaces when she was young. Her name was simplified to Audrey and she became the patron saint of Ely where an annual fair was held in her memory on the 17 October. Trinkets including cheap jewellery and a style of necklace known as St Audrey’s lace, which seems to have been a silk ribbon or string rather than a specific type of lace, were sold to the pilgrims. The term St Audrey’s lace became corrupted to tawdry lace and by the seventeenth century tawdry was used to describe anything cheap and vulgar.

Wednesday 30 November 2022

Damascene lace

Damascene lace is an adaptation of Honiton pillow lace invented in the late nineteenth century as a hobby lace. It incorporates Honiton lace sprigs and braid lace joined by corded bars and does not include any filling stitches. It can be quite simple to make if the Honiton motifs and the braid are ready bought or more complicated if the lacemaker works her own motifs and braid in pillow lace. To make the lace, the pattern is drawn on calico and the sprigs are tacked in place. Once they are positioned the braid is also tacked down following the pattern. Where the braid touches another part of braid the two are overcast together. The braid and motifs are then joined with bars made by running several threads from one to the other and making a series of close buttonhole stitches along their length. A little ready-made picot edging has also been added to the edge of this lace to finish it off neatly. Once all the elements are joined together the tacking threads are removed and the lace can be lifted off its calico backing in one piece. If the worker bought the components this would be a simple way to make dress decorations, such as this sleeve edge, as it required competent sewing skills but no lacemaking expertise.

Wednesday 2 November 2022

Lace bobbins with pewter inlays

These lace bobbins are all inlaid with pewter in different patterns – the bobbins with rings or stripes are called tigers, the V shaped ones are butterflies and ones with spots of pewter (not shown here) are known as leopards. The one on the far left has a thicker layer of pewter, which may originally have included lettering, and the second from the left also includes the inscription Joseph with the six letters separated half way through the name with the butterfly. The Springetts, who are modern bobbin makers, discovered that these bobbins were made by cutting grooves in the bobbin, placing it in a fired clay mould and then pouring the molten pewter into the grooves. They also found that the bobbin makers sawed an angled cut at the bottom of the groove to stop the pewter from coming loose. Pewter is an alloy of tin and lead, although sometimes antimony was added as well to make it look more shiney. In some of these types of bobbins the metal inlay is so shiney, through constant use, that it is often mistaken for silver but molten silver would set a wooden bobbin on fire and would damage a bone one so silver could never have been used and it would also have been too expensive for the lacemakers to afford. Unfortunately many inlaid bobbins have lost their pewter over the years, including part of the one on the far right, so it is common to find a bobbin with grooves but no pewter. In some cases the cause is corrosion of the pewter due to the interaction of perspiration from the hands on the tin in the alloy. This is especially the case for bobbins by Jesse Compton who ironically used good quality pewter with a high level of tin. The corrosion makes the pewter expand and feel rough to the hands and also to snag on the lace pillow so some of the lacemakers may have removed it on purpose to make the bobbins easier to use.

Wednesday 26 October 2022

Some clever machine lace production techniques

If you follow this blog you will remember that I recently received some samples of machine made lace from the 1970s designed for the lingerie industry. They also illustrate some interesting production methods used by the machine lace producers. For example, the image above gives an idea of how scalloped edged lace trims would have been made in one piece of lace with open net areas linking the two pieces, which would have been cut away once the lace came off the loom to separate the two scalloped edges, thus allowing the lacemakers to produce many strips of lace all together and save production time. The image below shows some strips of lace made in a similar way, linked together by joining threads which would have been pulled out once the lace was finished leaving the ribbons of lace.

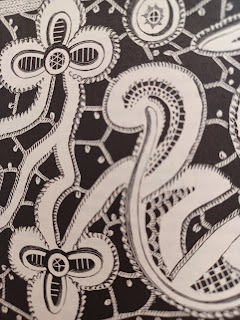

The pretty black lace below was made on the Levers lace machine.

It has a fine background pattern and an outlining thicker gimp thread

highlighting some of the motifs.

The heavier black thread would have been used to outline one

motif and then been allowed to run loosely down the side of the lace pattern

until it was required for the next motif, which meant that the loops of loose

thread had to be cut and trimmed once the lace left the machine. Both sides of this

lace also show remnants of the threads that joined it to the other strips it

was made with.

These two pieces of lace have picot edgings on both sides,

but the white piece still retains a thin thread along its righthand side which

was used to help form the picots and as a joining thread between this strip of

lace and the one next to it. Many of the joining threads between the strips of

lace were designed to be pulled out quite easily but some types had to be

removed by heat treatment using a tool like a soldering iron and others had to

be cut with trimmers. Much of this work was carried out by women working at

home on a piece-work system.

Wednesday 19 October 2022

Tatted lace

I need a small portable lace project to take on a trip I’m making and I thought tatting would be the ideal thing as it’s easy to pick up and put down and the equipment is quite small to carry about. I haven’t done any tatting for a while so I’ve been back to the instruction books to remind me how to make the double stitch that is a feature of the work. The image above is the edge of a little doily I bought years ago at The Lace Guild which shows the distinctive rings and loops that are used to make the patterns that are joined together as the work progresses by looping through the picots made at intervals between the double stitches.

I found tatting difficult to learn from a book as the secret

to the technique is the transfer of loops from one thread to the other – you’ll

know what I mean if you’ve tried it! The written instructions for this always tell

you to make the first half of the double stitch by looping the thread round

your fingers then passing the shuttle thread through the loop and then pulling

the thread taut with a sharp jerk – in my experience this always ends with a

knot on the thread not a loop. The secret is not a sharp jerk but a slight and

careful pull to transfer the loop. It is much easier to learn with two colours

of thread so you can see the transfer and also if a friend shows you how to do

it. I was lucky enough to have such a friend who showed me how to tat on a long

flight to the USA, which also means I always associate tatting with travel so

to take some on a trip seems very appropriate!

Wednesday 12 October 2022

Lingerie lace

Recently, a friend sent me some samples of machine made lace that her mother bought in Nottingham market in the 1970s and they are a lovely snapshot of the lace available at the time. I’m just showing a few here but I think they are all made for the lingerie industry. This was a time when women and girls wore petticoats, slips and vests as well as bras and knickers so there was plenty of scope for lace embellishment. The scalloped lace on the left would have been used on a bra as it can easily be cut to fit on a variety of cup sizes. The fine black lace would have made a lovely trim for a petticoat or slip. The straight white lace is an insertion, a type of lace which could have been used to join two pieces of fabric forming a beautiful transparent band of lace between them. The apricot coloured lace on the right is designed to include a ribbon slotted along its length so could be used as a strap for a petticoat or vest or could also be used as a trim without the ribbon.

These dainty white edgings are all laces that could be used

to trim any type of lingerie. The two at the top both mimic traditional

Buckinghamshire handmade bobbin lace styles and could be used to edge women’s

or girls’ underwear. The lower three samples are all elasticated but are a

little too narrow to be straps so were probably used as trims on vests and knickers

attached to fabrics that needed to be flexible. All these laces were made on

the Raschels lace machine apart from the black lace which was made on the Levers

machine. This difference in production methods is also an interesting thread

that I’ll blog about another time. Who would have thought that a bundle of lace

off cuts from the market would prove to be so interesting.

Wednesday 5 October 2022

Lace lappets

Lappets are long strips of lace or fine embroidery that were attached to women’s headwear and generally fell down onto the shoulders. As a writer in 1849 noted ‘lappets give grace, lightness and elegance to the whole costume’. A pair of lappets was usually attached to the back or sides of a cap but they could also be fixed to a bonnet or hat. They were fashionable for a long time during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and during that time their size, shape and positioning changed as fashions altered. For example a one time it was fashionable to pin the lappets on top of the cap and at others tie them under the chin. I have found it impossible to find an image of someone wearing lappets, which seems odd as they were such an ubiquitous style for so long, but Heather Toomer in her book on white embroidery suggests that this is because they were generally used for formal wear and most portraits depict informal settings. Pairs of lappets are found in many museum collections generally as separate strips of lace because they are so beautiful and when the fashion for them eventually ended it was possible to remove them from the cap and store them easily, therefore many have survived. Some have also been repurposed as scarves and dress decoration. Several were displayed in the Great Exhibition of 1851 including some in black Chantilly lace and others in blonde lace made of white silk thread as well as lappets of silk and gold from Caen. In the Paris Exhibition of 1867 lappets of Brussels needlepoint lace were exhibited. That they were made in many different styles of lace, were fashionable for so long and have been kept and donated to museums means they are a great source of information for lace researchers.

Friday 30 September 2022

Chemical, Swiss or burnt out lace

Chemical lace is basically embroidery on a sacrificial background that is removed once the lace is made. The lace in the image here would have been embroidered using the Schiffli machine which was developed at the end of the nineteenth century in Switzerland, hence its alternative name. There were various ways of removing the backing fabric once the lace was completed and Pat Earnshaw records several patents from the 1880s and 1890s describing different techniques. The two main methods are a chemical one in which the lace is embroidered on a cellulose material that is chemically removed or a carbonised method in which the lace is heated so the background becomes brittle and is then removed by brushing. The design here comes from a catalogue by Christian Stoll a company that was famous for this type of lace in the early 1900s.

Wednesday 21 September 2022

Dyed lace bobbins

I haven’t seen many dyed lace bobbins, whether this is because the dye has faded or because not many were dyed in the first place I don’t know. The Springett’s who have done most of the research on lace bobbins suggest that many of the dyes used in the nineteenth century faded in sunlight, which is why the necks are often a brighter colour than the shanks of the bobbin. Although the red bobbin on the right looks so bright you might think it has been dyed using a chemical dye it was probably coloured using cochineal, a dye derived from crushed Mexican insects and used in Mesoamerica since the second century BCE. The paler red bobbin was probably also dyed with cochineal. A chemical dye was probably used for the green bobbin, in this case copper arsenate. The bobbin on the left may have been coloured with a dye made from the chippings of the Central American logwood tree boiled in water. The bands might have been made by turning the dyed bobbin on the lathe to remove the colour in defined areas, but this bobbin also has two small holes, one at the top and the other at the bottom of the shank suggesting it may have had some bands of fine wire wrapped round it originally forming the bands. The Springett’s also report having seen yellow and mauve bobbins but in my experience the red and green ones are the most common.

Wednesday 14 September 2022

Lace connections

Connect is the prompt for today’s textile challenge so I thought I’d write about a couple of ways in which lace is connected both to other lace and fabric. The aim of most traditional lacemakers is to attach lace to a fabric with the tiniest stitches and in the neatest way possible, in fact books have been written on the subject of attaching lace as invisibly as possible. This blog is going to look at two alternative ways of connecting lace. The first is the illustrated above in a detail from my series The marriage bond looking at the work of Amy Atkin, the first female Nottingham machine lace designer, who had to give up work on marriage. I have deliberately made the connection between the lace and the fabric as obvious as possible by using tacking stitches in red thread to highlight the fact that the lace is not secure. In the same way that Amy’s career, and that of many other women at the time, could be ripped away in an instant.

The other

connection also links to women in the machine lace trade as it shows how ribbon

laces were made on the machines in one piece all joined together. A close look

at the image will reveal the thin draw thread running between the lines of lace

which had to be pulled out to separate them. This work was usually done by

women at home as piece work. They were not well paid but as the draw thread was

waste, and could not be used by the manufacturers, at least the women could

keep it and use it themselves. This reflects the use of the red thread in The

marriage bond which could also be drawn out in one swift movement and reused.

Wednesday 7 September 2022

My inspiration for research and practice

I’m taking part in the Seam Collective annual September Textile Love challenge again this year and today’s prompt is inspiration/influence so I thought I’d write a bit more about what inspires my research and practice. My research falls into two main areas, the history, manufacture and design of lace on one side and domesticity and women’s history on the other. I often combine the two with practice, for example my recent body of work ‘The marriage bond’ (detail above) looking at the life and designs of Amy Atkin, the first female Nottingham lace designer who had to give up paid work on marriage. It is made up of four dinner mats, in a reference to Judy Chicago’s feminist installation ‘The dinner party’, each has text from the marriage service and a lace design inspired by Amy’s archive of lace designs tacked in place indicating that the lace like her career could be torn away in an instant.

Other recent practice-based research includes ‘Marking time’ which is part of a series considering domestic abuse, in particular the coercion and control that is often an unspoken aspect of abuse as it leaves no bruises. My current practice-based research project is a series of handmade lace doilies incorporating text that considers the constraints of domesticity on women’s lives. Much of my ‘subversive stitching’ is also inspired by the way nineteenth century gothic writers expressed their radical ideas about women within fiction thus making it socially acceptable, and which inspired me to subvert domestic crafts, in a similar way, to convey a subtle feminist message.

As someone who enjoys gothic fiction it will be no surprise to discover that although I am interested in all aspects of lace, my particular interests are veils, net curtains and lace panels. I spend much of my time researching lace curtains, how they were made, the different styles in fashion at certain times and the designers who made them. A couple of years ago, I was delighted to be commissioned to carry out research into the Battle of Britain lace panel and its designer Harry Cross, research which led to a practice-based response and is still continuing as more of his archive has come to light.

If you are

interested in seeing more of my work there are plenty of images on my website www.carolquarini.com and I’ve also written

some papers for Textile: Journal of Cloth and Culture about some of this

research.

Quarini C. Domestic trauma: textile responses

to confinement, coercion and control. TEXTILE 2022 (published online January 2022)

Quarini C. Neo-Victorianism, feminism and lace:

Amy Atkin’s place at the dinner table. TEXTILE 2021 19(4): 433-453

Quarini C. Unravelling the Battle of Britain lace panel. TEXTILE 2020; 18(1): 24-38

Saturday 3 September 2022

Hamlet lace curtain panel

I saw this beautiful lace curtain panel depicting scenes from Shakespeare’s play Hamlet in the ‘Lace in the city of lace’ exhibition in Nottingham in 2015. It is machine lace and was made by the Nottingham lace company Simon-May & Co in the late nineteenth century. It was loaned to the exhibition by Malcolm Baker who worked for the company for many years and told me that this panel had been made and exhibited at an international exhibition in the 1870s. Huge decorative panels like these were made by several of the large lace curtain manufacturers at this time to demonstrate their skills and form the centrepieces for their stands at international exhibitions. Most of them follow the same design format with a central panel flanked by narrower columns of images on each side, although this one is unusual in repeating some of the side vignettes. Literary themes were popular, in fact at the 2015 exhibition I also saw a lovely panel based on the story of Don Quixote, also made by Simon-May & Co, which won a medal at the 1876 international exhibition in Philadelphia.

Wednesday 24 August 2022

Lace hair nets

Although we usually think of lace as decorative and ornamental, lace machines are also used to make hair nets. Reading ‘Century of achievement’ the book celebrating the centenary of the Simon-May Nottingham lace company I was intrigued by the section on lace hair nets. When the piece was written in 1949 hair nets were obviously big business for the company. I was surprised how many different varieties of net styles were used – six at least from the illustrations ranging from the very delicate square net to one fairly solid diamond mesh. The range includes ‘fine quality hair nets, warp nets for day and night wear, sleeping caps, boudoir caps and rayon snoods’.

The illustrations suggest that some have a tie that runs under the chin to secure them and others are slip on varieties. They also produce ‘triangular setting nets’ for hairdressers, presumably for the customer to wear while their hair was set and dried in curlers. They were all made in the company’s Long Eaton factory near Nottingham on Leavers lace machines in rayon, cotton or silk and were sold under evocative trade names such as Clingdon, Smartset and Will ‘o wisp. Hair nets were one of the few types of lace permitted to be made during the second world war, when thread was scarce and manpower reduced and women required hair nets to work in factories. The book notes that during the war rayon was used for most hair nets but a gradual return to pure silk threads was underway in 1949.

Thursday 11 August 2022

Subversive doily project

Recently, I’ve been spending a lot of time writing papers and chapters for books so today it was a real treat to spend some time making bobbin lace in a shady spot in the garden. I’m still working on my subversive doily project which uses the form of the lace doily to comment on the domestic environment and women’s place in it. The doily I’m working on at the moment follows the same design as the previous one with text in the central circle embedded in a lattice of plaits and leaves, surrounded by a border of Eastern European style tape lace. I finished the central area a while ago, which involved a large number of lace bobbins, and have now moved on to the tape lace border where I’m only using six pairs of bobbins. Although I’m not using many bobbins, this style of lace does mean that I have to keep stopping to attach the work to the edge of the previous row by looping one of my working threads through a previously worked pin hole and the passing the other working thread through that loop, which does tend to slow the work down. However, this part of the work is much less complicated than the central area so it is quite relaxing to sit in the sun listening to a podcast and making the lace.

Thursday 4 August 2022

Advertising lace curtains as imitations of ‘real lace’

At the turn of the nineteenth century even those selling lace

curtain were advertising them as ‘imitations of real lace’ and ‘very artistic

reproductions of real lace’. The image comes from a catalogue produced by the department

store Whiteleys in about 1910 describing some Nottingham lace curtains. The

curtains are sold in pairs and cost 9/11 for a pair measuring 4 yards by 72

inches, so quite a sizeable amount of lace. The claim to be an imitation of

real lace is obviously a marketing ploy to suggest the curtains are similar to

handmade lace, which was experiencing a revival at the time thanks to the philanthropic

efforts of various groups particularly in England, France and Belgium. However

the only link to ‘real lace’ seems to be in the design the outer border of

which is based on renaissance needlelace motifs.

The second image from the same catalogue claims to be ‘reproduction

cluny lace’. Cluny lace was a fairly solid bobbin lace with pattern areas

linked by plaits and leaves rather like English Bedfordshire lace. This pattern

does include some areas that look like leaves but the swags and ribbon shapes

seem quite alien to cluny lace so this may just be early advertising blurb.

The final image is labelled a ‘facsimile of old darned

knitting’. Why anyone would want old darned knitting at their windows is a

mystery to me, but this copywriter obviously thought it would appeal to

someone. The central area does look a bit like a blanket made from crochet

squares so perhaps that is what inspired the design.

Although these curtains have been labelled by the person

assembling the catalogue who probably knew little about lace (or knitting!), I

find it dispiriting that machine lace curtains aren’t being advertised as a

marvel of industrial ingenuity but rather as copies of ‘real lace’. They

clearly aren’t genuine copies of handmade lace so why not appreciate the design

and manufacturing effort that has gone into them.

Wednesday 27 July 2022

Three dimensional lace sculptures

Since I made a small 3D sculpture entitled inside:outside for the Tansa exhibition earlier this year (see the March blog) I’ve been playing about with a few other shapes that can be manipulated into mini sculptures. I do like the way they can be moved about and altered although I think this piece would need some quite strong stiffening to keep its shape. Perhaps adding a thin wire round the edge would be a good idea.

As you can see from this image the piece is basically a

strip of Torchon lace worked in thin separate sections all linked at some point

but allowing quite a range of twisting and movement. I like the effect especially as it shows off the open nature of the lace and will

keep playing about with the theme when I get a bit more time.

Wednesday 20 July 2022

Revival of needlepoint laces

I’ve been reading about the revival of Venetian style needlepoint laces throughout Europe during the 1880s as part of my research into ‘imitation’ laces. These heavier more structured laces became fashionable as trimmings on clothing at this time. This led to lacemakers copying examples of seventeenth century laces but also in many cases remodelling actual pieces of old seventeenth century lace. Belgian lacemakers famed for the expertise of their needlelace copied many of these seventeenth century designs so skilfully that it is thought some Venetian merchants ordered the lace and sold it for high prices to visitors to Venice as genuine seventeenth century work. It is very difficult to distinguish it from the original lace although one tell-tale sign is the use of cotton thread instead of the original linen thread as cotton thread was not used for lace making until the 1830s. However, hand lacemakers soon had competition in the form of chemical lace made by embroidering patterns on to a sacrificial backing material which was then chemically removed and which superficially imitated the more solid Venetian styles very well. The lace in the image is a modern interpretation of needlepoint lace.

Wednesday 13 July 2022

Lace shawls, collars, pelerines, scarves, berthas and fichus

These shoulder coverings were all popular at different times during the 19 century and in many cases it is difficult to classify them. Scarves and stoles look very similar as do pelerines, fichus, berthas and collars depending on their width and when they were made. The examples here all come from the lovely ‘Lace in fashion’ exhibition which is currently on display at Wardown House Museum in Luton. Not only do they show the range of different fashions they also show how lace changed during the century from the entirely handworked, such as the fichu made in Bedfordshire Maltese lace, to a beautiful black machine lace collar.

There is a lovely wide Duchess collar of mixed Brussels

bobbin and needle lace showing how the two types of handmade lace were

traditionally combined and the image shows a detail of a beautiful dress including

both types of Brussels lace applied to a machine lace background showing how handmade

and machine lace were often combined. There is also a fichu combining pillow

lace with machine lace as well as scarves with Honiton bobbin lace applied to

machine made net. Several of the other collars have a machine net basis including

a Limerick lace collar and another tamboured shawl. Other Irish laces popular

in the second half of the 19 century are also represented with a Carrickmacross

applique lace bertha, and an Irish crochet collar. I was also interested to see

some examples of ‘imitation’ lace following on from my recent blog posts. The

exhibition includes two Chantilly lace shawls one handmade and the other

machine made; difficult to tell apart without close inspection as would have

been the case when they were worn. There is also a chemical lace pelerine worked

in the style of Irish crochet and a late 19 century collar worked in the style

of 17 century lace, so lots of copying and convergence going on. If you want to

see more you will have to visit the exhibition which includes much more lace

than the few pieces I’ve described here and is well worth a visit. It is open

until 11 September.

Wednesday 6 July 2022

Bone lace bobbins recording deaths

Two of these bobbins commemorate sad occasions, the one on the right is inscribed ‘Eliza Ward is no moor’ and the middle one says ‘Eliza Hall my dear sister died Feb 5 1866’. Many of these types of bobbins recording deaths also state the age of the deceased but perhaps that was more common if they were exceptionally old or young. T L Huetson, who carried out extensive research into lace bobbins, records that in some cases a piece of bone from the meat served at the funeral meal was used to make memorial bobbins. I don’t think this is the case here as both bobbins are of good quality and don’t give the appearance of coming from an ordinary joint of meat. The bobbin maker David Springett in ‘Success to the lace pillow’ says he was initially sceptical of this tradition as contemporary meat joints do not have thick enough bones for bobbin making but he notes that animals in the 19th century were fatter, larger boned and slaughtered later in life so could have had bones of the required thickness. Also many village families kept a pig which was fed on scraps and could have provided bones for the occasional bobbin. However, most 19th century bone bobbins are made from horse or oxen bone, both of which were widely available at the time. The third bobbin in the image may also be linked to the central one. It is inscribed ‘David Hall my dear son 1866’. I bought these two bobbins together, but I don’t know if David and Eliza Hall were nephew and aunt. However, it is a coincidence that the bobbins were made in the same year by the same maker and I found them both for sale in the same place. There is no indication why the lacemaker chose to commemorate her son in 1866 – I hope it was to record his birth or some other happy occasion.

Wednesday 29 June 2022

Copying lace styles

Having seen ‘imitation lace’ being described in my late 19 century needlework dictionary as a type of tape lace (see last week’s post) I was interested to see how Pat Earnshaw defined it. She wisely does not use the term imitation lace but does discuss copying and convergence in her book on the identification and care of bobbin and needle laces. She suggests seven possible permutations of copying, starting with ‘same time; different area; different technique’ in which she includes all the machine lace copies of different handmade lace techniques, such as machine-made Chantilly lace. Chantilly lace is the fine black lace seen in the image above and the handmade and machine-made versions are often difficult to tell apart. Initially I thought the example above was machine made because of the way the outlining has been done but on closer examination I found the lace had been made in fine strips, later joined together, which is a feature of handmade Chantilly lace.

Under ‘same time; different area; same technique’ Pat

mentions the convergence between Bedfordshire lace and Maltese lace, as well as

that between Honiton and Brussels laces (image above). In ‘different time;

different area; same technique’ she includes the raised needlelaces of the 17

century, which were copied in the 19 century for sale and exhibition as well as

for the domestic lacemaker as we saw in my previous post about imitation lace. There

were also laces in the category ‘different time; different area; different technique’

such as the 16 century reticella designs that were copied in the 19 century using

the Schiffli machine. I think Pat Earnshaw has confirmed my original scepticism

about the label ‘imitation lace’. Most laces seem to be influenced by ideas and

techniques from other places, and as Pat suggests sometimes this is copying and

sometimes convergence. However it was always with the aim of selling more lace

to the consumer, by keeping up with fashions and making the lace more cost

effectively.

Tuesday 21 June 2022

Imitation lace – one late 19 century view

I was amused by an entry in my 1882 Dictionary of needlework on imitation lace, as surely that is a description that could apply to most types of lace. However, it seems that the focus of the entry is those types of lace made from machine-made braids and handmade fillings that were popular with the domestic audience who would have been reading the Dictionary. The book gives five examples of different ways the technique can be used and the end results are very effective considering the simplicity of the materials. The imitation Venetian lace in the image above is a simplified version of Venetian gros point; an elaborate needlelace that was made in the seventeenth century. To make the lace you have to trace the design on to calico then tack down machine-made, half inch wide, cloth braid, doubling it where necessary and smoothing it round the curves – by no means an easy task! Then run a fine cord all the way round the edge of the design. When that is done, the open parts of the pattern can be filled in with needlelace stitches of your choice and the main elements of the pattern are then joined together by buttonhole bars. Finally, you have to work buttonhole stitch over the raised cord, all the way round the design in the same way as the original Venetian lace. You can further embellish this raised cordonnet by working a lace edging along its length if you like. The lace can then be removed from its calico backing.

Another example is an imitation Honiton lace. For this one,

three types of braid are required; a straight one for the edge and two types of

braid made up of continuous leaf shapes, one of half stitch leaves and the

other of cloth stitch leaves. The lace is made on a calico foundation as above

and you start by tacking down the foundation line of braid at the top. Then the

half stitch leaf braid is tacked in place, up and down, just touching the upper

braid, to make a zigzag edge. The cloth stitch leaf braid is then laid over the

half stitch one, in the same way to make a zigzag, filling the gaps. However,

for this one, every other cloth leaf is folded over to make it look like a leaf

stalk. Another straight braid is laid under the pattern and the leaf pattern

repeated using just half stitch leaves. Where the braids touch they have to be

sewn together and bars added to join the sections together. The instructions

blithely suggest sewing ‘an ornamental lace edging to the lower edge of the

pattern’. This piece certainly seems easier to work than the imitation Venetian

lace, but all the designs assume the reader has a detailed knowledge of

needlelace stitches and the skill to carry them out with little instruction.

Wednesday 15 June 2022

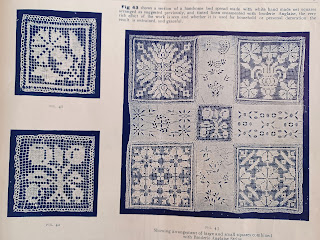

Early twentieth century filet lace

I’m delighted with my latest purchase – an early twentieth century booklet about filet lace which explains how to make it and use it around the home and in clothing. Filet lace was a popular female hobby at the time as were a number of other needlecrafts. This booklet is number 66 in a series of practical needlecraft journals. Most of them assume quite a high level of competence from their readers and this one is no different, although it does recommend a further booklet in the series if the reader requires more help with making the foundation net.

Filet lace is made using two techniques. First the

background net is made with a shuttle and it is then ‘darned’ with a needle and

thread to make the pattern. However, it was possible to buy readymade net which

must have been a boon to many lacemakers because ensuring evenly spaced net is a

skill and if not done well can ruin the entire piece of lace.

Filet lace was mainly used for decorating household linen as

shown in the section of a bedspread above, which combines filet lace squares

with a type of embroidery called broderie anglaise. The booklet also suggests

several collars, edgings and insertions for blouses and you can see an example

of the front cover of the magazine.

Tuesday 7 June 2022

Nineteenth century English lace schools

Lace schools were generally held in a room in the teacher’s house and little was learned apart from lacemaking. The teacher charged a small fee of about 4 or 5 pence per week for each child – often slightly more for boys because they were naughtier and not as biddable as the girls! Children started at the lace school at 5 years of age and remained as pupils until they were about 14, but the boys often left earlier to work in the fields. The day was long, starting at 6 in the morning in the summer and 8 in the winter, and the children had to produce a set amount of lace every day. Every 4 or 5 weeks the lace buyer came to the village to buy lace from the adults working at home and the children at the school. Known as ‘cut off day’ the children were often allowed the afternoon off from lacemaking once the lace had been sold. By 1880 most of the lace schools had closed. One reason for this was the 1867 Workshop Act which prohibited the employment of children under 8 years of age and allowed only part time work for those aged between 8 and 13. Education was also made compulsory in 1871 and all children had to go to school for at least part of the day to become literate and numerate. Lacemaking was still taught in schools in the lacemaking areas but as part of the normal curriculum rather than as a trade or money-making activity.

Wednesday 25 May 2022

Netted lace

Netting has been practised for centuries and was used by early people to make fishing and bird nets and can also be used to make hammocks and lawn tennis nets. However the type of knot used for lace netting, seen in the image above, is slightly different and less bulky than that used for these utilitarian articles. Netting was a popular pastime in the early nineteenth century and in her novel of 1847, Charlotte Bronte describes Jane Eyre sitting in a corner netting a purse while she observes Mr Rochester and his guest in the drawing room after dinner. My 1882 Dictionary of Needlework gives several instructions for making a variety of netted purses for ladies and gentlemen as well as doilies (like the one below), antimacassars and a variety of other items.

Netting is made from a continuous thread wound on a netting needle and the knotted loops are made, starting from a foundation loop attached to a cushion, round a stick to ensure all the loops in the row are the same size. Skill is required to keep the work even as the knots are hard to undo once they are made! The basic net structure can be varied to make different patterns including star netting, looped netting or fringes, and it can also be embellished with beads. Once the net has been made it can be embroidered in the same way as drawn thread work or be used as the basis for filet lace. What seems like a simple technique can actually be made in many decorative forms and shapes.

Wednesday 18 May 2022

Confetti beads in lace spangles

The spangle is the ring of beads attached to the end of English East Midlands bobbins to give them weight and ensure they lie flat on the pillow. They are generally made up of six square cut beads (three each side) with a larger bead at the base, although there are many variations. The larger bead is often more ornamental than the others and those in the image all have added dots of glass. The one on the second right is a confetti bead which was made by adding small chippings of brightly coloured glass to the surface of the bead as it was being made just before it solidified. The large green bead seems to have had the white dots added after it was made as they are slightly raised. The bead at the top is known as an eye bead as it has a series of dots on top of each other, loosely resembling an eye. The most famous of these types of bead is the Kitty Fisher eye bead, which is made of grey glass with small red and blue spots inside larger white spots, supposedly representing the beautiful face of the actress. These dotted beads may have been made locally or purchased from travelling salesmen as many beads were made commercially for trade in Africa and would also have been available for lacemakers to buy (see my blog post of 24 September 2021).

Wednesday 11 May 2022

Machine lace curtain draught

Apart from being a beautiful painting this is the draught, or coded instructions, required for a curtain made on the Nottingham lace curtain machine. A draughtsman would have painted it by hand following the original design drawn up by the designer. The draughtsman therefore had to be artistic and also know about the workings of the lace machine in order to translate the design into a workable pattern. This draught would then have been passed to the card puncher who would follow its instructions to produce the sets of jacquard cards needed to work the pattern on the lace machine. In general, red squares indicate back spool ties and green indicate Swiss ties, although there is no standard colour code and some manufacturers used different colours. This draught also has handwritten instructions along the length of the pattern describing among other things the width of the entire piece of lace (360 inches) and the type of lace (two gait Swiss). It also tells us that this is a 10 point lace which means that it is of medium fineness. I think these lace draughts are beautiful but the fact that they carry so much coded information makes them even more special.

Wednesday 4 May 2022

Filet lace curtains

The patterns for these lovely curtains appear in a booklet of filet lace from the early twentieth century. In the index they are labelled as a store curtain and matching brise-bise curtains in the style of Louis XVI. They could have been used on the same window with the store curtain hung on the upper part and the brise-bise curtains hung against the lower panes or they could have been used separately. Brise-bise curtains are what we know as café curtains and only cover the lower half of a window.

The instructions for making the curtains, which are all in

French, suggest that the lace should be worked in blocks of 1 centimetre. The

dimensions given are 141 blocks for the store curtain and 85 x 55 for the

smaller ones. I assume from looking at the pattern that the measurement given for

the store curtain is the width. This booklet gives no instructions for working

the filet lace but another volume I have, from the same time, shows how to make

the background net and work the stitches so I think the expectation was that

the lacemaker would know how to do both.