These two lace bobbins both fall into the category that T L Huetson labelled ‘saucy’ inscriptions in his authoritative book on lace and bobbins. One is inscribed Kiss me quick and the other Kiss me quick [my] own true love. There are lots of variations of these sentiments such as Kiss me quick my lovely darling and Kiss me quick and dont be shy. Huetson also records a pair of bobbins inscribed Kiss me in the dark and Love doo it again. He suggests that the owner of the last two may well have blushed over her lace as she read them! The bobbin on the left was probably made by the bobbin maker the Springetts describe as the ‘Blunt end’ man who worked in the middle of the nineteenth century near Bedford. That on the right is most likely the work of Jesse Compton who lived at Deanshanger and was making bobbins in the first half of the nineteenth century. Jesse Compton has an interesting history. He was the son of a Wiltshire farmer and in his early twenties travelled to Lincolnshire, but was arrested for vagrancy and after a public whipping and time in prison he was sent back to Wiltshire. However, he seems to have stopped off in Buckinghamshire where he married and settled down as a labourer, becoming a turner and bobbin maker in later life. He and his wife had six children the oldest of whom also became a bobbin maker.

Wednesday, 16 December 2020

Wednesday, 9 December 2020

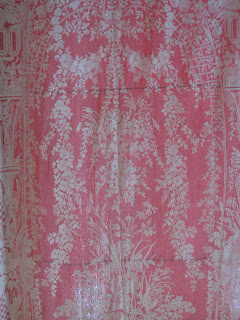

Chantilly lace

I bought this lovely sample of Chantilly lace in Bruges last year. Chantilly is one of my favourite laces because of its delicate shading and the way it looks when it’s worn against the skin, for example as a veil. Santina Levey notes that the Chantilly lacemakers originally made blonde lace, usually in white or cream thread, but because of changes in fashion they began making black lace in the 1840s using grenadine, a non-shiny silk thread. Chantilly lace uses a light twisted Lille ground for the net, while the motifs in the design are worked in half stitch and outlined in a heavier gimp thread.

Any bobbin lace is time consuming to make, and Chantilly is

no exception. For larger pieces such as veils and shawls, which were

fashionable in the mid to late nineteenth century, several lacemakers worked

strips of the lace that were later joined together using invisible stitching

called point de raccroc. Unfortunately this line of sewing is also a weak point

that sometimes comes undone showing where the strips of lace were joined (see

above). Although my sample is coming apart, I found it interesting to see the way

in which the strips had been divided so that the join interfered as little as

possible with the main parts of the design.

Wednesday, 2 December 2020

The Space Between lace catalogue

What a treat – my copy of the catalogue of ‘The Space Between’ handmade lace exhibition, curated by Fiona Harrington for Headford Lace Project, arrived today and I’ve been enjoying browsing through it. I was going to blog about my favourite pieces but I realise that it’s impossible to choose between them so I’ll give you an overview of the exhibition instead. As Elena Kanagy-Loux reminds us in the introduction, lace is a textile defined by its appearance and numerous techniques are used to make it, many of which are found within this exhibition.

As expected, many of the pieces showcasing techniques celebrate Irish laces. Sr Madeleine Cleverly’s chalice cover edged in Headford lace links the past and the present, while Rosie Finnegan Bell’s Carrickmacross lace tree (see above) celebrates the legacy of lacemaking in South Armagh. The heritage of Carrickmacross lace is also the subject of Karen McArdle delicate photobook. The Irish Crochet lace hat exhibited by the Irish Crochet Lace Revival Group beautifully incorporates three types of Irish crochet to display the intricacy of the technique. The fine working of another traditional Irish lace, Borris tape lace, is displayed in Helena McAteer’s round floral d’oyley. Ann Keller describes her bobbin lace fans as Irish Celtic style bobbin lace, which rather than spotlighting one specific type of Irish lace are designed to include Celtic traditions and art within their folds. Of the other lace techniques, Jackie Magnin uses Torchon lace with variations of her own, Olga Ieromina plays with the size and placing of traditional lace, and Tali Berger makes large scale bobbin lace structures using rattan.

Many of the pieces were made as a response to lockdown during the Covid-19 pandemic. One of these is ‘Le Messenger’ by Elisa Gonzalez made using free bobbin lace techniques inspired by the colours and the view of a garden. Daniela Banatova’s intriguing abstract bobbin lace forms (see above) are inspired by the trees and rock formations she finds on her travels. Also in the exhibition is one of Mary Elizabeth Barron’s Torchon lace river series based on the Logan River, made from threads she has created from clear plastic packaging to highlight the impact of plastic waste on the environment. Moving from the earth to the sky, Ashla Ward’s complex black crochet pieces were inspired by exploring the darkness in the spaces between the stars in the night sky. Kim Lieberman also incorporates images of the sky in her bobbin lace piece, which comes from a series of works inspired by territories. Her images are taken from banknotes around the world and the chaotic (or wild) ground which holds the currency in a flux explores the interdependence of us all.

Nature on a smaller scale is depicted in Andrea Brewster’s

tatted coral forms and Eleanor Parkes’ needle lace insects. Eithne Guilfoyle’s image

of red deer shows the versatility of Limerick lace, while Theresa Kelly’s

vessels (see above) inspired by tree bark show the contemporary possibilities for

Carrickmacross lace. M Merce Rovira and Atena Pou were also inspired by nature,

their free bobbin lace sculpture captures the feeling of a soft breeze under an

oak tree. Rather than depicting nature, Saidhbhin Gibson interacts with it by, for

example, temporarily covering scars on trees and cacti with delicate needle

point lace.

Moving from embellishments for nature to those for the body. Roisin de Buitlear’s lace engraved glass visor reminds us of veiling. It speaks of fragility and vulnerability and as such it is a tribute to front line workers in the Covid-19 pandemic. Malgorzata Szpila showed two lovely bobbin lace necklaces, one of falling golden leaves (see above), and the other of frozen silver leaves. Angharad Rixon used silver wire worked in free bobbin lace over a stone found on the beach to reflect the passing of time (see below) and Jane Fullman also worked bobbin lace in wire to produce beautiful patterned pendants and flowers. Suzanne Plamping’s delicate circular hanging inspired by reflection also uses metallic threads. In contrast to these smaller pieces, Kara Quinteros used large scale experimental bobbin lace to produce a bodice and skirt using ethically sourced yarns.

Family ties are celebrated by Rachel McGrath who uses Irish crochet lace and hair to capture an essence of her past. Two artists exhibited self portraits: Eleanor Parkes’ is representational and made from bobbin and needle lace, while Vesna Sprogar’s is pixelated and composed of bobbin lace and tatting. Ester Kiely also uses technology in her bobbin lace installation ‘Port San Aer’ (see below), which translates music into lace, and you can also listen to the tune by using the QR code in the catalogue.

Mary St. George, who introduced lacemaking to Headford in 1765, is celebrated by Norma Owens in a series of small round sculptures that incorporate symbolic motifs to represent her life and reflect on the male commentators who tried to belittle her work. Other artists dealing with women’s issues include Amy Keefer whose capsaicin crochet collar considers the lack of means of defence for women throughout history, while Camilla Hanney’s ceramic lace gloves suggest excessive femininity and explore the contradictions involved in traditional handmade lace production. Marian Nunez exhibits two metaphorical works that consider the emptiness of life and the ephemerality of beauty, based on Japanese iconography. Ger Henry Hassett’s moving work ‘A black mark’ remembers the souls of the 796 skeletons of babies who died and were buried at the Tuam Mother & Baby Home and the mothers who were scarred by their experiences there (see below).

As well as these beautiful and thought-provoking pieces, which

were exhibited in an art trail in windows throughout Headford, there were two

commissioned works of art. Unfortunately these are not illustrated in the

catalogue so I haven’t seen them, but the artists are Selma Makela who painted

a triptych remembering those who traditionally made lace in Headford and Tarmo

Thorstrom who alters the scale of Torchon bobbin lace by making it in linen and

jute rope.

Despite not being able to travel to Headford I have thoroughly enjoyed visiting virtually through the catalogue. As Elena says in her introduction, lace is not a dying art rather we seem to be ‘on the precipice of an exciting revival’. It is encouraging to see contemporary lacemakers exploring new paths as well as celebrating the revival of traditional lace. If you would like to discover more about the Headford lace project or order a catalogue for yourself you’ll find all the information on the website www.headfordlaceproject.ie

Wednesday, 25 November 2020

Thomas Lester and Bedfordshire lace

Thomas Lester was a nineteenth century Bedfordshire lace manufacturer who was responsible for some of the most beautiful English lace designs. The image above is taken from a cap piece he designed which is now in the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford. He exhibited lace at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London where he won a prize medal for his ‘improved arrangement of Bedfordshire pillow lace’. This was probably not an original design but an adaptation which showed that he understood the process of lacemaking and had an eye for designing. It is thought that he may have been able to make bobbin lace and his wife was definitely a lacemaker. In the 1850s there was a move away from the traditional point ground lace in Bedfordshire to the plaited laces which subsequently made Lester famous.

This image shows pages from Lester’s exercise book of

designs in the Cecil Higgins collection. He was designing point ground lace in

the early 1850s but after visiting the Great Exhibition, and in particular

seeing that Honiton lace was not only a more free style of design but also was

held in higher regard and fetched a higher price, he began designing Bedfordshire

lace in a freer style using plaits to join the elements rather than grounds,

which he used as filling stitches instead.

The designs often feature realistic plant forms and animals

and the source of these may have been books of natural history, illustrated

periodicals or Owen Jones’ The Grammar of Ornament which was used as a teaching

aid at art schools. Such realistic natural designs were popular at the time and

feature for example in Honiton and Brussels lace as well as other textiles. In

the 1862 International Exhibition Thomas Lester was awarded a medal for his new

type of lace, which he called ‘Bedfordshire white fancy lace’. He died in 1867

but the Lester family continued their lace manufacturing business in Bedford

until 1905 and won medals in several exhibitions including the one in Chicago

in 1893. However, the success of machine lace reduced their business

considerably, particularly following the 1860s when the Levers lace machine became

capable of producing imitation Bedfordshire (Maltese) lace, and they

diversified into art needlework and Berlin work as well as continuing to sell ‘real

lace’.

Wednesday, 18 November 2020

‘Frayed nerves’ needle lace

Walking the dog today and looking at the bare branches of the trees reminded me of this piece of lace I made a while ago. Based on nerves rather than branches it still reminds me of this bare, raw season of the year and the feeling of wind and rain tearing everything off the trees, leaving things exposed and vulnerable. It also seemed quite apposite to a time of lockdown and isolation. It’s made of needle lace cordonets and I kept the frayed ends to embed into silk paper and also to reference the title of the piece. As you can tell I’m not an autumn person but I am trying to tune in to the beauty of the season by reading the anthology on Autumn compiled by Melissa Harrison and it is changing my view. I’d always thought of autumn as just a wet cold time we had to get through in the run up to Christmas and then look forward to the spring but Melissa has shown me that it can also be a time of renewal and beauty.

Thursday, 12 November 2020

‘For better; for worse’ Amy Atkin lace mats

I’ve had a busy week writing about my response to the life and work of the first Nottingham machine lace designer, Amy Atkin, who although very successful had to give up work on marriage. The idea for using lace mats came from the work of the second wave feminist Judy Chicago who used place settings for famous women in her monumental installation ‘The Dinner Party’. She used complete place settings for her guests but I’ve just made place mats for Amy Atkin. Each one includes a strip of lace inspired by her lace designs, but only tacked in place, to show how easily women’s careers can be taken away from them and that domestic duties still have a huge influence on women’s lives. Each one also has part of the wording from the marriage service embroidered on it ‘for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer’ to reference the fact that she had to give up work when she married. Studying Amy Atkin’s life and lace designs, feminism, and the work of Judy Chicago has been interesting and making a practice based response seemed the appropriate approach to the research so writing about it is a great way to pull all those strands together.

Wednesday, 4 November 2020

Lace making in Bobowa, southern Poland

I’m delighted to let you know that I’ve just had a review published in the journal of Craft Research volume 11 (2) about a book on Polish lace makers. The book is by Anna Sznajder and is called ‘Polish lace makers: gender, heritage and identity’. The link to the current issue and my review is CRRE 11.2 but I’m afraid there are no free offprints with this journal. The book was based on research the author did for her PhD in the lacemaking community in Bobowa, southern Poland, and although it is obviously an academic and thoroughly researched book it is also very readable. It describes how lacemaking was brought to the area in the late eighteenth century and became a cottage industry in the nineteenth century. Throughout the twentieth century various organisations encouraged lace teaching and design but by the end of the century lace making was more of a hobby than a business. However, since 1995 lace making in Bobowa has been revitalised following the introduction of the International Bobbin Lace Festival and the setting up of the Gallery of Bobbin Lace in the town. The author makes lace and clearly has an interest in the lives of these Polish lacemakers. She is interested in the politics, both national and local, that have affected lace making and her interviews with lacemakers allow insight into the changing details of the local lace making industry and women’s role within it. She concludes the book with suggestions on how activities linked to the lace heritage could encourage more tourism to the area. It’s an interesting book, and well worth reading especially if you have been or are planning a visit, to the Bobowa lace festival..

Wednesday, 28 October 2020

Spangles on antique lace bobbins

Spangles are the circles of beads attached to the end of English East Midlands style lace bobbins. Their function is to add weight to the bobbin, to provide tension for the thread, and to prevent the bobbin rolling on the pillow. The most common type of bead in nineteenth century spangles is the square cut glass bead. In an interview with The Bedfordshire Times in 1912, Robert Haskins the bobbin maker explains that they were made by melting a piece from a stick of glass on a copper wire, which made the central hole, and then pressing the sides with a file which caused the markings on the bead and its square shape. Eye beads were also popular and some can be seen in the image above. These were round beads with spots of colour added to their surface to give the appearance of eyes. The most well-known were Kitty Fisher beads celebrating the famous actress, with blue and red dots representing her mouth and eyes. Beads were not the only objects on spangles however, many of them incorporated seashells, coins, buttons and beads that would have had a personal meaning to the lacemaker.

Wednesday, 21 October 2020

#MeToo doily bobbin lace

As you can see my new bobbin lace doily is underway. The idea of using a tape lace construction was that I would need fewer bobbins and I wanted to see if it was a quicker way of working. Well that hasn’t been the case so far, mainly because I’ve started at the most difficult place where I’m incorporating the text #MeToo into the design. However working the grid filling has been interesting as I’ve only needed two pairs of bobbins for the entire thing, as they just work up and down there are no four plait crossings as there would be in Bedfordshire lace, which is the style I’m most used to. Instead of crossings, one of the pairs is hitched under the previously worked plait and the other pair linked through it to make a join. The books about tape lace suggest only one thread need be hitched under but I found that didn’t make a neat join and using a pair works better for me. It’s also a learning curve trying to work out the right length for each plait in the filling when you complete the ‘crossing’ on the following row, I think I’m getting the hang of the tension but I find four plait crossings easier. I guess it’s just what you’re used to! I wanted the text on the mat to stand out so I gave up attempts to include the text in cursive script and I’m using Bedfordshire style techniques to work it, hence the increased number of bobbins. Once the text is finished I should be down to a handful of bobbins for the outer mat though. It’s certainly an interesting way of working and great to be learning some new techniques.

Wednesday, 14 October 2020

Troubled love lives in lace bobbins

I’ve been winding bobbins for my latest bobbin lace project – the mat I’ve been designing in tape lace, which I’ll blog about once the lace is underway – and I came across these three bobbins about troubled love lives. They are inscribed with Love don’t forsake me; Let no false lover gaine my hart 1842; and Its hard to love and canot be love again. One poor lacemaker is trying to hang on to her boyfriend, while the other two have clearly had romance problems in the past. The one who doesn’t want a ‘false lover’ suggests she’s had one in the past who cheated on her. While the last one implies she’s found a boy she likes but he’s not interested or that she too is having problems getting back into a relationship. At least it shows that these problems did not start with social media – they’ve been going on for centuries! In fact T L Huetson in his book on Lace and bobbins records one with the inscription ‘Place no confidence in young men’ – a warning that any young girl would be wise to bear in mind! I think the first bobbin on the left was made by Bobbin Brown of Cranfield, the middle one was probably made by Jesse Compton and the one on the right is probably by David Haskins who came from a family of bobbin makers.

Wednesday, 7 October 2020

Lace pattern designing

I’ve decided to continue my series of subversive lace mats with a message. The first one was made in Bedfordshire style lace and had ‘get off me’ worked into the lace. It’s been exhibited in many places and always draws interest so I thought I’d make a series of them which could be shown together. However, this time, as I’ve become interested in Russian tape lace, I’ve decided to use that style for the new mat. I’ve never made that type of lace before so it’s a bit of a leap in the dark and my piece will definitely be in the ‘style’ of Russian lace rather than being a model example!

I’ve found Bridget Cook’s book ‘Russian lace making’ to be very useful and, as you can see from the picture above, I’ve started designing my pattern. The great thing about this type of lace is that if you design the pattern well you can make the entire mat in one go with only a few pairs of bobbins, there is very little tying in and out. I have incorporated what I would call a ninepin edge in part of the design just so I can make it in the Russian style with only two pairs of bobbins! You start working from one edge of the main pattern and work a plait for the lower half of the edging, joining it to the footside as you go, then when you reach the end you turn back and work the top half of the edging, joining into the bottom half as you work until you return to the place you started from – isn’t that clever! That’s the theory anyway, I’ll let you know how it turns out! My main problem at the moment is how to include the text into the central area of the mat and what filling stitch to use. I’m not sure if I can make the text in a continuous line, I may have to work that part as a separate motif and tie into it. It’s definitely a work in progress and I’m learning new things all the time!

Wednesday, 30 September 2020

Pillow lace by Mincoff and Marriage

Having recently revisited and blogged (12 August 2020) about the lace books written by the Tebbs sisters I have been browsing other early twentieth century bobbin lace instruction books on my bookshelf. Elizabeth Mincoff and Margaret Marriage published their book in 1907 as a result of learning how to make Torchon lace on a holiday in Freiburg but finding on their return to England that there were few patterns or instruction available. The book is quite comprehensive with chapters on equipment, history and design as well as clear instructions on how to make a series of lace designs. They explain that, unlike some other authors, they have not used codes or symbols in their instructions but instead rely on clear diagrams and short explanations. They begin with some ‘Russian’ or tape lace patterns with simple instructions and pleasing results, which only require a few pairs of bobbins on the pillow so are ideal starting pieces (the image shows the first three pieces taught in the book). They then progress to Torchon patterns requiring more bobbins and then move on to Maltese and plaited laces. The book is written as a course and it is suggested that the reader works through the chapters sequentially. The Tebbs sisters also start the beginner off on tape lace which I did think was a good choice as it is fairly easy to achieve good results with it, which is encouraging for the student, and also easy to understand the design method for those who want to produce their own patterns.

Wednesday, 23 September 2020

Earth fan bobbin lace

I have finally finished the piece of bobbin lace based on earth for the fan series I’m working on inspired by the four elements. I’m pleased with the colour combination and putting it together with the lace for the other two I’ve recently finished (air and fire) they work well together. I made the water fan a while ago for an exhibition in Valtopina, Italy and I want to make the other three in the same way so they form a group. For that fan I embedded the lace in silk paper and used a simple wire frame to make the fan shape so I’ll do the same with these. I’ve been looking through my silk fibres to see what colours I have and I think I’ve got the right colours for earth and air but I may have to dye some for the fire fan. I also need to make the wire shapes to attach them to. Perhaps my excitement on finishing the lace was misplaced I still seem to have quite a lot to do for this project!

Friday, 18 September 2020

New lace projects

The beginning of the autumn and the return to school is always an exciting time as it heralds the beginning of a new academic year and new projects. I have to admit I’m still finishing one of my lockdown projects – the series of bobbin lace fans inspired by the four elements but I’m half way through the lace for the last one based on earth so I feel I’m getting on well with it. I also have a couple of new lace projects underway, one inspired by the research trip to Japan I went on last year with other members of the UCA textile department, and another which is an extension of my lace doily work on subversive domestic lace. The Japanese work is interesting because we are all making work expressing our impressions of Japan and it will be shown in two parts, one is made up of miniature work and the other comprises larger pieces. Most excitingly, for the miniature exhibition we will be joined by many of the Japanese artists and masters we visited in Japan who are also generously contributing miniature works so it will be an Anglo-Japanese exhibition. The exhibitions are entitled Tansa – the Japanese word for exploration – and the miniatures exhibition will be shown at the Craft Study Centre in Farnham and Gallery Gallery in Kyoto (dates are given on my website www.carolquarini.com). I’m also busy writing two papers about different machine lace designers so I have plenty of new projects to start the autumn!

Wednesday, 9 September 2020

Antique bobbin lace pricking

This antique bobbin lace pattern, or pricking, probably dates from the nineteenth century. It is a simple narrow insertion with a footside on each edge and a simple pattern of flowers and leaves running down the centre and would have been made using a Bedfordshire style of lace with plaits linking the different elements of the pattern, rather than the net ground used in Buckinghamshire lace. We now tend to use cardboard for our prickings but this one is made of parchment which suggests it is quite old. It is very sturdy and was made to be used many times, over and over again. The pattern is pricked before the lace is begun using a pointed pricker tool, often using a previous pricking as the template by pricking through it onto the new parchment.

The cloth attached to the ends would have made it easier to

handle the pattern without making it greasy from too much handling and was the

point at which the pattern was attach to the lace pillow. Thomas Wright in The

romance of the lace pillow says that most parchments were about 14 inches long

(this one is about 10 inches) and each was called a ‘down’. Thus the lacemaker would

say she had made a down when she finished the length of the pattern. He also

says that the linen ends were called ‘eaches’ which means an extension. Variations

on the spelling are eche, eke and etch and the term is linked to the phrase ‘to

eke something out’ meaning to extend it to make it last longer.

Wednesday, 2 September 2020

Striver pins in bobbin lace

Pins play an important role in bobbin lace, they are the temporary structure around which the lace is produced but some special pins have other functions. The two pins in the image are called strivers. They are made from two brass pins and could only be made because the heads of these nineteenth century pins could easily be removed. One pin was threaded with beads and also had its head replace with a bead. It was then attached to the head of another pin. These strivers were used in the Midlands lace counties of England to see how quickly a strip of lace could be produced. T L Huetson in his book ‘Lace and bobbins’ says the striver was inserted ‘in the hole in the parchment pattern’ and the lacemaker then checked how long it took until she had ‘worked out all the other pins and come to the striver again’. This sounds a bit hit and miss to me though because first of all it depends how many pins you have and also when I work a lace pattern I don’t take the pins out in a set order but just remove them randomly from the back when I need one! Using the striver in the footside would be a more accurate point to measure from as it couldn’t be removed until a certain number of pattern repeats had been made and the lace was secure. Actually using the striver in the lace, rather than just pinning it next to the pattern, would have meant it couldn’t be moved easily so it would be difficult to cheat! Using strivers would certainly have been a useful way to incentivise children learning to make lace and encourage them to compete with their peers to be the quickest in the class. I also think that English lacemakers liked to brighten up their lace pillows, for example with colourful spangles and interesting bobbins, and this was another way of doing that.

Wednesday, 19 August 2020

Make up your mind lace bobbins!

These two lace bobbins were owned by lacemakers who wanted to know where they stood. The one on the right says ‘My dear love me or leave me alone’ an admonishment to a young man to make a commitment to the lacemaker or to stop flirting with her. ‘My love, love me’ is a little sadder and perhaps suggests unrequited love or it may just be a hint to a shy young man. This supposes that the lacemaker purchased the bobbins herself. If in fact the bobbins were bought by young men and given to the lacemaker they tell a different story. Perhaps the lacemaker is the flirt and she is the one who is proving elusive to the young man’s charms. The bobbin with the long inscription also has an unusual addition to the spangle in the form of a sea shell which could have been a present from a sailor in the family. The bobbin on the right was probably made by James Compton as it has his style of head, tail and lettering. The one on the left seems to be the work of Arthur Wright who is known for his bobbins with pointed tails and a cruder style of lettering than the Comptons. Both bobbins were probably made in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Wednesday, 12 August 2020

The Tebbs sisters and the art of bobbin lace

Louisa Tebbs was a lace teacher in the early twentieth century, first at the Northern Polytechic in London and later at her own School of Bobbin Lace and Embroidery in Baker Street, where she was assisted by her sister Rosa. They produced two hugely successful books, in 1907 and 1911, about lace design and lacemaking and taught numerous pupils. I’ve recently been having another look at the books after reading a very interesting article by Gwynedd Roberts about the sisters in the latest issue of Lace, the Lace Guild magazine. The Lace Guild is planning an exhibition of 20th century lace in which some of the Tebbs’ original patterns and lace samples will be exhibited, which will be worth a visit.

Louisa taught what she describes as sectional bobbin laces, such as Italian point de Flandre, Bruge guipure, Duchesse , Honiton and Bruxelles. In other words those laces that are worked in sections and only require ’18 bobbins (often less) for the most elaborate patterns’. Her instructions are clear and practical. She notes that she ‘encourages the pupils to rely whenever possible on their own intuition and intelligence’. She also encourages them to design their own patterns as she feels that will engage their interest and also suggests that pin holes are not pricked in advance but made by the worker as she progresses to suit her individual work.

The new student begins with the ‘Italian’ lace edge of shamrock shapes shown above but soon progresses to the Honiton flounce shown here. The books also include instructions for various filling stitches and patterns for lace that can be applied to net, like the Honiton flounce, as well as Honiton raised work. The books are clear and very encouraging but I think the pupils had a better grasp of needlework than we have today, for example there are no instructions for attaching the lace to fine net it is just assumed the reader will know how to do this. If you can find them the books are an interesting read, as is Gwynedd’s article, and the exhibition at the Lace Guild should be interesting too.

Wednesday, 5 August 2020

Tape lace designs

I’m still considering using tape lace for a series of lace doilies incorporating text, which I want to make to highlight issues relating to women. I’ve made some preliminary sketches but am still not sure whether to run the lettering from the same tape as the border into the centre of the mat or whether to make a circular mat first and then add the lettering with other filling stitches to the centre afterwards by sewing in. I’ve done some rough sketches trying out both alternatives and I think I prefer the text that runs on from the border into the centre, mainly because the lettering is slightly less defined and therefore more hidden within the doily. I want the result to be quite subtle and the lettering not to be too obvious. The aim is that people look at the mat and think ‘Oh another lace doily’ and then realise what it says and that it is a doily with attitude! I need to mull it over for a while until I’ve made a final decision and then draw up a working pattern.